Broken-out toilets sitting about in the city streets are funny but only for a while.

Berlin and I have always been in this weird dance between attraction and repulsion, but it’s only recently that living here has started weighing on me. Navigating its sensory topographies — the sirens, the smelly waste in the streets, requires a certain level of bodily disassociation. I notice how I unconsciously impose separation between my body and the bodies around me. I withdraw inwards and seek refuge in my imagination outside the present moment. In the wild, the reverse happens. In the presence of countless othernesses, my attention drifts outward. Boundaries seem more fluid when I am engrossed in the ongoingness of life unfolding. After a few days, I become in tune with the place. I become more of it.

That’s why in early autumn last year when some friends from my hometown came to visit, I scouted for those wild places that could ever so briefly offer a sense of fugitive soul weaving. I scanned satellite images on Google Maps looking for nature reserves and big stretches of unbroken forest. Eventually, I picked Harz, a national park in Saxony-Anhalt with the region’s highest elevations, only a two-hour train ride from Berlin. On the map, it looks like an island of deep greens, encircled by an extensive patchwork of farmland and roads; the beating heart of a body mutilated by monoculture and an ecologically monotone culture.

Allured and attracted, off we went.

Our Airbnb sits in a valley between two small hills. We are staying in an old renovated cottage with wooden sidings freshly painted in gold, peanut brown. The garden lies atop a steep hill. In the middle stands eloquently a plume tree bearing an abundance of fruits, so much that its heavyweight makes it bend over. Scattered across the ground are dozens of purple plums, many trampled over and many more being savored by tiny critters. Nature loves giving.

As I walk further up the hill, I notice how quiet it is here. Strangely quiet. To my surprise, the hills are not populated by trees but barren. Plucked bare. Fallen trees cover the hill slopes as if a deadly gush of wind swept through the entire forest only moments ago.

Are we in the right place?

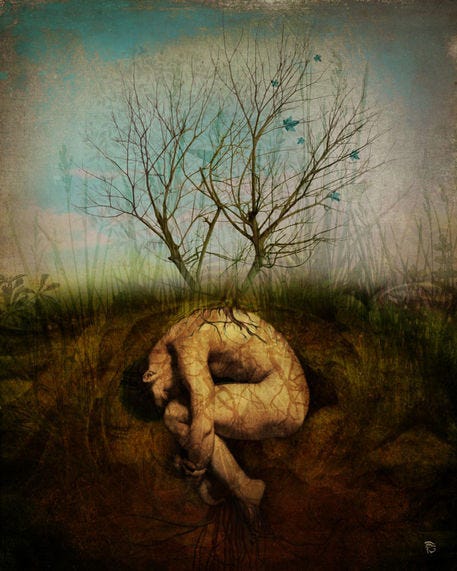

There’s a forest within me.

We follow the quiet murmur of the stream uphill along moss-covered boulders casting shades of deep green. Oaks and beeches populate the banks of the river. Their leaves slowly turning orange-yellow as they prepare for their perennial descent. We sit down for a moment. I breathe in the fresh air and the radiant colors and feel how tension in my body dissolves. An oak leaf flutters downward in a spiral-like motion, lands in the river, and gets gently carried away downstream.

“Every outside has an inside”, sings the robin in my chest.

As we make it to higher ground, the topography starts to change unexpectedly. The vigorous forest we traversed just an hour ago is now exchanged for what should be an evergreen forest, only that the dominant colors are not green and orange-yellow but brown and gray. All that is left are the naked skeletons of spruce and tree stump carcasses as far as the eye can see. And alongside sudden perceptual changes, the emotional landscape changes too. As I overlook the endless horizon of dead trees something within me shifts. I no longer feel that same intensity of aliveness as I felt before. Instead, I notice a sudden pressure on my chest, a tightening of my heart. The hike becomes like a march for unknown warriors in the wake of a battle, except that these trees aren’t self-enlisted soldiers but “pitiful” casualties of a man-made war they didn't choose for.

Is this also sorrow?

It’s been several months since I visited Harz, and I’ve been trying to integrate the experience ever since. Rather than ignoring and moving on from what I felt during that trip, I went deeper into those feelings. Scientists have extensively researched “nature bathing”, and more than a thousand papers suggest that walking in nature has a positive effect on depression and our overall sense of well-being. But why is it that I suddenly felt depressed walking through those clear-cut landscapes? Why was I suddenly transported into a very different state of mind? Modern psychology would be quick to conclude that I am somehow projecting my inner experience onto this place or that I’m holding on to an ideal of the forest — a pre-determined image of how it ought to be or look. But that answer somehow seemed too easy to me. It was far from satisfying.

Instead, what if we’re tuning into topographies of feelings that exceed us? What if feelings are dynamic, ever-shifting qualities of a place or a larger whole that we participate in? Maybe “emotions” are not just inner states we flip through but an ongoing, planetary process of emotioning or how the earth experiences itself through us and the millions of organisms and entities with whom we co-create this planet. Perhaps I was receiving the grief of the forest, responding to clouds crying out for their earthly companions, black crows circling the sky cawing because death was wrought upon their land.

In his book “These Wilds Beyond Our Fences: Letters to My Daughter on Humanity’s Search for Home”, author Bayo Akomolafe writes of the in-between spaces as the breathing grounds for thoughts and feelings:

“Thoughts don’t come from within, neither they come from without. They emerge between. It’s the same with feelings. I like to think that the gentle dipping of a leaf under the weight of a dew drop can set off a series of events that float through us as what we call depression, and that the molten formation of a rock through the intra-activity of weather, technology, and story is experienced with joy in a specific moment. I like to imagine that when a seed falls into the earth, it experiences grief, and its grief is met by the loamy femininity of the soil, and that’s how trees sprout out with joy. Perhaps those moments of unspeakable silence, when depths churn and sides groan, when words escape you, when a pill or a diagnosis doesn’t add up too much, when all you want to do is squeeze yourself into the tiniest place in the universe, it is because you, for all intents and purposes, are co-performing the disintegration of imaginal cells within a cocoon and knowing the pain of becoming a moth.”

What if grief doesn’t belong to you but to the earth? What if the emotional pain you wish you could forget beneath buried grounds is actually the fertile seed in an ecological process that ensures the prosperous continuation of life?

Perhaps the sorrow I felt walking through the devastated forest was a concoction of the spruce kin’s penetrating eyes staring at me in hurt hostility and the resounding sorrow of the earth itself.

While all this may sound far-fetched and odd to Western ears, and it certainly did to me before, understand that this is not some new esoteric theory, but how our ancestors experienced the world in their bodies and through their embodied perception. Many indigenous peoples still do. In the Spell of the Sensuous, author David Abram quotes cultural anthropologist Richard Nelson, who wrote about the Koyukon people from north-central Alaska and how they “live in a world that watches, in a forest of eyes. A person moving through nature however wild, remote, even desolate the place may be is never truly alone. The surroundings are aware, sensate, personified. They feel. They can be offended. And they must, at every moment, be treated with the proper respect.” Perhaps the sorrow I felt walking through the devastated forest was a concoction of the spruce kin’s penetrating eyes staring at me in hurt hostility and the resounding sorrow of the earth itself. “The country knows.”, said the Koyukon elder, “If you do wrong things to it, the whole country knows. It feels what’s happening to it.”

In the last centuries, we’ve been taught to believe that nature is the scenery, a garden you stroll through, the backdrop to our human conversations. The Christian church vilified pagan traditions that revered and honored the divine nature in everything directly, conceiving the role of the church as the middle man mediating between mundane and divine realms. We lost the rites and rituals that sustained and renewed our moral bonds and obligations to the more-than-human world. Science believed that we are supreme subjects separate from an inanimate world of objects from which we could derive objective truths. Abstract, conceptual thinking as processes of the thinking mind were epitomized, while embodied, sensory knowledge was frowned upon and suppressed.

Although the grounds are shifting, I notice that even in contemporary discourse, interbeing is often portrayed as the idea that everything is interconnected. Animism is a concept, and we are to understand conceptually that we are woven into webs of relationships. Yet in my experience, interbeing means actively participating in the world through my awakened senses and an open mind and heart. It is the refusal to become objectified and abstracted from the fluency of emotions; to tune into and experience them. Let the moving world move you.

Do you truly feel you are woven into webs of relationships with all life? Do you feel in your body the reverberations of a dew drop that settles on the web of our relatedness? Have you felt the pain when your local forest was cut down as your pain? For, to paraphrase Charles Eisenstein, when your context changes, you also change. "If a forest is cut down that you had a relationship to, then something in you is cut down as well. Something in you changes because we are not separate."

Every time I numb or suppress my feelings, I'm gradually exiling myself from my body. I am choosing the path of separation. And the danger in exiling myself from my feeling body means parting the connective membrane that weaves my body into a felt relationship with the larger body of the earth. In a culture that teaches kids to transcend the confines of their body in the metaverse, swallow painkillers for a minor headache, sit indoors and listen 7 hours a day to a teacher naming each part of a mitochondrial cell while they daydream about life outside, rewilding our emotional perception — and enabling others to rewild theirs, is a radical act. It’s how we unlearn decades of social conditioning to distrust our emotional perception and learn again to feel life.

What I call for is not just a guilt-ridden solastalgia but an invitation to become better listeners to a world that is always speaking to and through us. This is a feeling-thinking process that requires discernment. And as I’ve learned, the more I do this, the more information that will reveal itself to me, and the more I cultivate my capacity to understand and act on the creative forces that constitute places and experiences. It’s an intelligence that is perceptive and receptive and generates respons-ability to act in ways that respect, enlist, and regenerate bodies beyond our own.

In his book Earth Grief, Stephen Harrod Buhner introduces what he calls climate of mind. He writes:

What a person feels when they unexpectedly come upon a human-damaged forest is a combination of two things: the kind of wound (and its ramifications) that touches them and the particular climate of mind of the people who destroyed the wholeness that was once present… That particular climate of mind is integral to every form of ecological damage we encounter. It is now in Earth itself in so many locations it cannot be escaped. We are immersed in, surrounded by, such wounds... and the climate of mind that produced them. When the aesthetic dimension of a thing is compromised or damaged a particular feeling emerges from the heart. There's a wrongness to what has happened and that wrongness has a particular, unique feeling dimension to it. And there's a great deal of information inside the mood or atmosphere that arises. Contemplation of its textures will reveal that information, give a far greater understanding of what has happened than any reductive analysis can or ever will.

Buhner encourages us to notice the feeling response we have to an environmental wound such as a clear-cut forest. Our perceptual analyses become more accurate and sophisticated if we immediately compare this response with that of a healthy forest, for, he writes, “it is by comparison, and an analysis of differences, that we learn to distinguish the subtle characteristics of things.”

When I walked along the river lined with deciduous trees and vividly colored leaves, I noticed a sense of elation and wonder within me. The wildness without activated the wildness within. I perceive an aesthetic sense of vigor and aliveness in the external world that produces a similar vigor and aliveness within myself. But as soon as I walked up the hill and overlooked the infinite horizon of dead trees, something gradually changed. Depression and sadness overtook me. I realized I entered a different climate of mind. Upon deeper analysis, I noticed the vast majority of saplings and the lack of diversity and old-growth trees in the valley — two ingredients indispensable to a healthy and resilient forest. Conifers were planted in clear lines without much space between one another, reminding me of grid structures in cities. The forest was dead silent and I couldn’t hear any birds. Some trees’ bark was stripped, making visible dozens of intriguing engravings in their trunks that looked like alien artistic messages. I later learned that these were the doings of beetles that feed off the living tissues below the bark and that — due to more favorable conditions caused by human-induced climate change, propagated ever more quickly and contributed to the death of thousands of trees. This process most likely began with the industrial revolution when large swats of native forest were destroyed and replaced by fast-growing spruces to fuel the mining industry. In the decades that followed, forest health declined, making it increasingly vulnerable to pests. It almost seemed as if the ecosystem as a whole was undoing itself from centuries of degeneration and monoculture and a climate of mind that believed nature was only a resource to be extracted to enable human progress.

Integral to the climate of mind that led to centuries of destruction is also our inability to grieve the life we lost — and to see non-human lives as worthy of our grieving.

In many conversations, when presented with this kind of information the first response I often get is “So, what do we do about it?”. Understanding what really happened doesn’t mean we should immediately get all praktisch about it. Brush aside the remaining infected trees and simply plant new ones. Sure, it’s part of the work, but it isn’t all. Handling notary papers after someone’s death isn’t the funeral, and it surely isn’t the years of mourning that come after it. Integral to the climate of mind that led to centuries of destruction is also our inability to grieve the life we lost — and to see non-human lives as worthy of our grieving. What if the whole community came together to honor a clear-cut forest? What if for a brief moment, we could join in ritual and let go of blame, rationalizations, and ideologies and see the situation as it is — the loss of life and of something dear and deeply familiar, something so invaluable that sustained us in all our material and spiritual needs? Which deeper emotions and truths could this communal gathering held within an environmental wound help surface? And how could it rekindle the feeling qualities or spirit of a place that would rekindle us in turn?

Praise storytelling is how we tap into deeper layers of our interwoven experiences, and how we expand our language to express the often poetic ineffability of those experiences.

When we pause and allow our separation from the living earth to rise, we feel the "grief and sense of loss" that Shepard speaks of. When we open ourselves and take in the sorrows of the world, letting them penetrate our insulated hut of the heart, we are both overwhelmed by the grief of the world and, in some strange, alchemical way, reunited with the aching, shimmering body of the planet. We become acutely aware that there is no "out there"; we have one continuous existence, one shared skin. Our suffering is mutually entangled, the one with the other, as is our healing.

— Francis Weller, The Wild Edge of Sorrow

Rituals to mourn death also carry within them kernels of opportunity to share stories of belonging and praise. Stories of memorable encounters with those wild others and childhood memories of building camps and treehouses and playing hide and seek between pines and nettle bushes. Praise storytelling is how we tap into deeper layers of our interwoven experiences, and how we expand our language to express the often poetic ineffability of those experiences. It’s how we channel the voices of the more-than-human and how we express gratitude for their breathing presence.

Now that ecosystems are collapsing quickly and the cultural stories we live by seem to be losing the coherence and potency they once had, these rituals are becoming extremely vital and precious.

My roots continue growing underground years after I’ve been felled and my belly has been laid bare. My lifeblood, the nectar of my teary sap, seeps outwards. I nurture the life that comes after and through me. Occasionally, I burst through the dark, damp soil again, searching for light and new life. I am not the large ash I once was but the bright-green sapling that contains me. Fragile and tender, yet infused with the essence of my being.

I see you. Have you seen me? Have you burst out in joy and laughter after your sappy tears mixed and mingled with mine? For you, I am the outside to your inner experience, and you an outside to mine. We are entangled in this sacred bond of feeling, a testament to resilience and renewal and a creative life force that emerges between us.

We reach a steep cliff dotted with giant stones and an old-growth beech with large overhanging branches. This site breathes ancientness. We are in the presence of elders. I feel safe and seen and wholly at peace in this place of reflection and repose. I am reminded of elder trees in Berlin parks that make me feel grounded yet seem so far away. We all need to hold onto roots sometimes and feel overshadowed by life much older and bigger than us.

How do I allow myself to stay open to the feeling world even when the dense human world around me feels invasive? Where are the wild places I turn to when our collective despair and grief feel too much to hold?

An invitation

I would like to end with an invitation. Next time you go out into nature, and you feel like you need to “make conversation” with your companion, try instead to pause, listen, and tune into your feeling, animal body, and notice how it responds to the body of the earth around and beneath you. What sounds do you hear and what smells do you observe? Do you feel at peace or is something off? Once you have fully felt everything there is to feel, reflect on the climate of mind — the thinking, beliefs, and mindset, that is the undercurrent and the cause of why this place looks and feels the way it does. What does it feel like to wander through a meadow or through a field of tree stumps? Write down, draw, or paint your observations. Repeat this practice again in urban environments. How do the people around you and the urban design affect you? Where are the places that make you feel at home?

The earth is summoning us back, calling on us to respond. Are you listening?

Deeply moving, thank you. I listen, I feel, I grieve our collective thoughtless brutality, but where there is evidence of the old world life thriving, where there is space for the robin to sing, I breathe and relax.

Utterly profound Niels. I've shared it on Tribe. Warmly, James